Abraham Lincoln...the Preacher?

When Lincoln Addressed a Wounded Nation with a Sermon-like speech

Note: 159 years today Abraham Lincoln addressed the nation to deliver his Second Inaugural Address as president of the United States. It was also roughly a month shy of Robert E. Lee’s formal surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox in Virginia. How does Lincoln address a nation who has endured the deadliest war in its history and after his victorious presidential bid? Interestingly, his address is more like a sermon that spoke to a wounded nation.

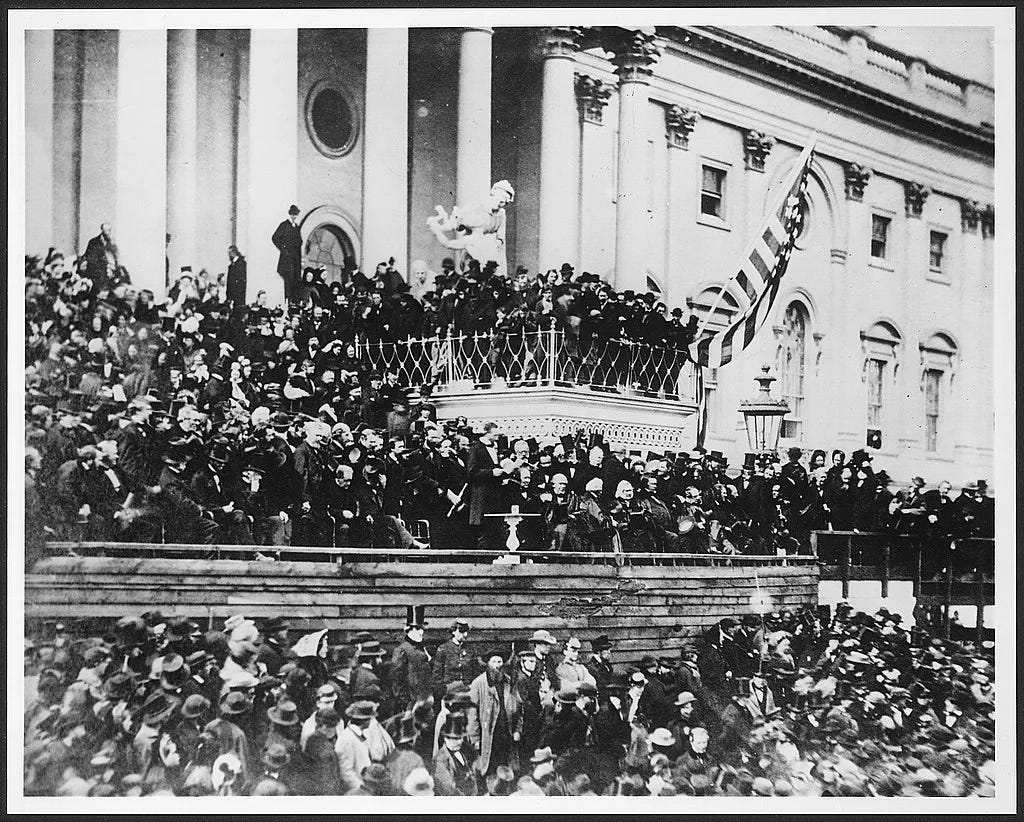

On Saturday, March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln towered over a seemingly small lectern on a platform just outside the U.S. Capitol building to deliver his Second Inaugural Address. It had rained much of the morning, and it was cold.1 The gloomy, damp, and frigid weather conditions mirrored the state of the nation that Lincoln faced to address.

But the weather did not stop the sixteenth president from delivering what would become one of the most important addresses in American history and perhaps the most powerfully theological statements ever uttered from the mouth of an American president.

Lincoln was addressing a nation just weeks shy from the conclusion of a long and bloody Civil War that came at the expense of at least 650,000 lives.2

Lincoln—and many White House officials—had no idea who would be present at the inauguration.

Rumors spread that Confederates—cognizant of their imminent defeat—may be present to create an uproar in a last ditch effort or worse, attempt to assassinate the president who sought to upend their Southern way of life.

Despite the unknown of the hundreds of thousands of people gathered outside the Capitol that gloomy Spring Day, Lincoln—even before the presence of his soon-to-be assassin, John Wilkes Booth—faced to address a wounded nation.

Lincoln’s speech would be far from triumphant. It was more melancholic than celebratory.

Lincoln could have easily used his address to cast blame on the political architects of the Southern Confederacy. He could have called down derision and retribution on Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee—and a host of like-minded Southerners—for their deliberate betrayal of the country at Fort Sumter almost exactly four years prior to the day of Lincoln’s address. After all, this is what the religious leaders of Lincoln’s day had been doing since the outbreak of war in 1861.3

Rather than succumbing to the sentiments of Northern or Southern preachers, Lincoln’s address served as a pastoral meditation amid the most tragic moment of American history.

Frederick Douglass, who was present in the crowd that morning, encountered Lincoln at a White House reception following the inauguration. Lincoln inquired what Douglass thought of his address, to which Douglass responded by describing his address as “a sacred effort.”4 Douglass later observed, “The address sounded more like a sermon than a state paper.”5

According to Lincoln, only God could have seen the calamity that was to come of the Civil War. Despite the apparent division between the Union and the Confederacy, Lincoln addressed a few strikingly odd similarities they had with one another by using unifying language such as “neither” and “both,” to bring them together.

First, Lincoln states that “Neither party [Union and Confederacy] expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained” and “Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease.”6

This move Lincoln makes is a strategic attempt to unify a country that has been at war with itself. And, undoubtedly, as Lincoln makes clear, the conflict that evoked and sustained the war was none other than human enslavement.

Secondly, Lincoln famously states that “both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.” He continues, “The prayers of both could not be answered, [and] neither has been answered fully.” Lincoln narrows in on the religious layer of the war.

In clear and unquestionable language, Lincoln pinpoints that both the Union and Confederacy understood themselves to be participating in a divinely ordained task.7 Each found divine empowerment and inspiration to fight so fiercely and adamantly against the other by calling on the same God, whom both sides believed was “for” them. “If God be for us,” both sides believed, and as the Apostle Paul declares, “then who can be against us?”8

Thus, the other side could not stand a chance of standing between them and God’s will, as each understood it. Their diametrically opposed conclusions expose the theological conundrum at the heart of the American Civil War.

Three years prior to his address and one year into the Civil War, Lincoln privately wrestles with this tension, as he writes in “Meditation on the Divine Will” that “Both [the Union and Confederacy] may be, and one must be, wrong. God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time.”9 In other words, God could not answer both prayers in the affirmative. Therein lies one of the greatest ironies in American history.

Delivering the second shortest inaugural address in United States history consisting of seven hundred and one words in twenty-five sentences organized in four short paragraphs, Lincoln communicates the depths of the religious tension found at the heart of the American Civil War.10

Lincoln publicly wrestles with the age-old theological dilemma over the relationship between divine sovereignty and human liberty. While both sides interpreted their actions as a judgement from God on the other, Lincoln, like an Old Testament prophet, flips the switch by placing both sides equally under the same condemnation and evokes the judgement of God. “The Almighty has His own purpose,” Lincoln declares, “and that [God] gives to both North and South this terrible war” as divine judgment on the entire nation for the sin of slavery, a sin for which all Americans, Lincoln argues, were complicit.

Donald G. Mathews, Religion in the Old South (Chicago, 1977), 159.

Estimates that between 650,000 and 850,000 people died throughout the Civil War. For more, see: J. David Hacker, “A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead,” Civil War History Vol, 57, no. 4 (December 2011), 07-48.

For more detail on the context of Lincoln’s address, see Ronald C. White, Jr.’s essay, “Lincoln’s Sermon on the Mount: The Second Inaugural” in Religion and the American Civil War, ed. Randall M. Miller, Harry S. Stout, Charles Reagan Wilson (Oxford University Press, 1998), 209-211.

Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (Hartford: CT, 1882), 404-407. 7 Douglass, Life and Times, 403.

Douglass, Life and Times, 403.

Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address” March 4, 1865, in Abraham Lincoln, Slavery, and the Civil War: Selected Writings and Speeches ed. Michael P. Johnson (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001), 320-322.

Noted Civil War historian, James M. McPherson, notes in his “Afterward” of Religion and the American Civil War, that “[the] Civil War armies were, arguably, the most religious in American history.”

All scripture will be quoted from the King James Version, unless otherwise noted. The quoted passage is from Romans 8:31. See Wayne Flynt, Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie, (The University of Alabama Press, 1998), 111.

Abraham Lincoln, “Meditation on the Divine Will,” September 2, 1862, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 403.

Ronald C. White, Jr., “Lincoln’s Sermon on the Mount: The Second Inaugural” in Religion and the American Civil War, ed. Randall M. Miller, Harry S. Stout, Charles Reagan Wilson (Oxford University Press, 1998), 211. George Washington’s Second Inaugural Address in 1793 was just two paragraphs, one hundred and thirty-five words, constituting the shortest inaugural address in United States history.

Hm, this feels super relevant right now. This is a compelling and helpful reflection, thank you.